It’s August – dog days, the vamp-til-ready for the fall, the months in which the school year that impends begins to fill children across the land with unnameable dread.

But August brings with it a perquisite, too: if your next career move points you toward a stint in baseball’s major leagues, August is the month for you.

By that bit of vocational counsel I’m directing you to a truth – which can hardly be held to be self-evident – disclosed by studies that corroborate a small but palpable disproportion among major leaguers born in August (along with a Freakonomics post citing birth-month advantages turning up in an array of sports).

The standard accounting for the August baseball edge goes something like this: Little League teams enforce a July 31 birthdate cut-off for any season’s eligibility, and so boys (and girls nowadays) born in August – the oldest and likely the more physically prepossessing of their peers – continually dominate, and through the experience are thus better positioned to ultimately win that call-up to the majors.

Truth to be told, my contrarian self resisted the claim. As the Rabbis say, it appeared to my impoverished mind that the performance differential stoked by so scant a datum as birth month couldn’t materially pump up, or by extension depress, a player’s employment prospects. But what do I know? It seems as if the numbers respectfully disagree with me; so let’s then see what they might mean, and where else we might take them.

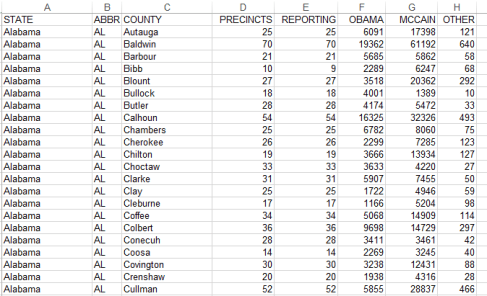

My data spring from an Excel workbook I’ve adapted from the storied, freely-downloadable baseball player database managed by Sean Lahman (who won’t turn away contributions, by the way), one of the go-to sites out there if you’re into these kinds of things (it purports to contain, after all, statistics for every season played by every major leaguer since 1871).

The workbook about to unfurl on your screen reports basic demographic information about the players, and Lahman was kind enough to jam in a birthMonth field into the mix, exempting us from the chore of wheedling months from birthYear (not necessarily a big deal, in any event via the MONTH function, similar to the WEEKDAY we encountered in a previous post). You can get the workbook here:

But before we fashion the pivot table that’ll help us replicate the birth-month claims, time first to put some spreadsheet into spreadsheet journalism. Some of the records before you are missing birth month data (primarily from pre-1900 players); and as these can’t help us here, I sorted the worksheet by birth month, having the effect of consigning the vacant birth month cells to the very bottom of the ream of records (this should happen whether you sort by smallest to largest or in the other direction). I then inserted a new row in 17454, thus severing the blank birth month records from the usable remainder. So why not simply delete these inert records, then? Because I may want to recover them for some different analytical purpose later, and should that eventuality present itself I need only delete row 17454, and restore the records below it to the larger body of data.

In any case, now we can insert a pivot table and slide in these fields:

Drag birthMonth to the Row Labels area.

Drag birthMonth again to the Values area (we’re in effect breaking out birthMonth by itself). Change the Sum operation to Count if necessary (click anywhere in Sum of birthMonth, and then click PivotTable Tools tab at the top of the screen, click Options> Summarize Values By> Count.

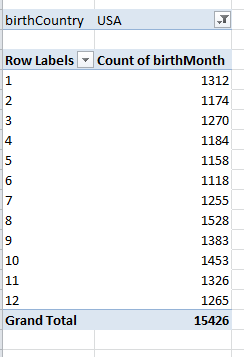

Drag birthCountry to the Report Filter, and why? It’s because we want to confine our scrutiny to American-born players (at least initially) – the ones most likely to have played in Little League. Click the Filter arrow, and select USA (tip: you can accelerate that trip to the lower reaches of the alphabet by typing U). You should see:

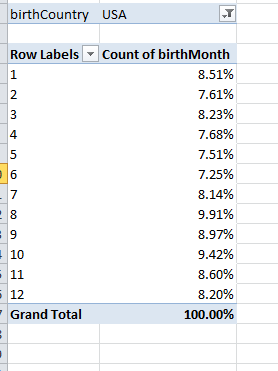

Note the quite discernible August margin (month 8). To concretize this outcome, click anywhere in Count of birthMonth, Show Values As (assuming haven’t strayed from the Options button group) > % of Column Total. Now you’ll see:

That’s fairly definitive (remember our universe comprises 17,000+ records, so questions about statistical significance should be safely pre-empted). Note in addition that the next largest birth cohorts populate September and October, findings which would appear to comport with the theory, too, as would the shortfalls in April-June (even the diminutive February tops May and June). Only the uptick in July seems anomalous, its offspring the youngest per the Little League’s July 31 threshold. One wonders if some Little League affiliates hold to a June 31 demarcation instead – something to research.

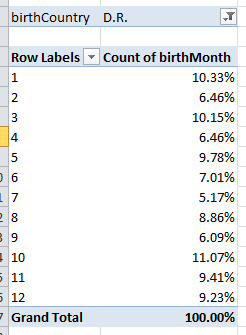

In any case it all seems pretty confirmatory, particularly if for comparison’s sake you apply the filter to a different country – say the Dominican Republic, a nascent demographic power in baseball’s workforce. Replace USA with D.R. in the filter (that’s how the country is represented here) and you’ll see:

(Universe size here, by the way – 542 players).

Not terribly much pattern in this case, but what we do see is that August doesn’t own the modal representation here – October does, and by a lot (a predominance in its own right that might justify investigation). August’s 8.86% here doesn’t distance itself very far from the chance expectation of 8.49% peculiar to any 31-day month. (Of course you can now filter for any country, and if you want to assess birth months against the actual number of players contributed by that country, drag birthMonth a second time into the Values area and do the Summarize Values By > Count thing. Note then that both Value fields will sport the Count of birthMonth rubric, but the first of these will have been subjected to that special % of Column Total tweak. I’m sure, by the way, that my co-residents in London will be pleased to learn about the 34 major leaguers born in the UK.)

OK – this is all interesting and instructive, but something tells me we’ve withheld a term from the larger equation. After all, explanations of the August syndrome invest in the Little League eligibility rule, as it were – that July 31 cut-off. But the Little League didn’t debut until 1939, and hadn’t widened its ambit beyond the state of Pennsylvania until 1947. And it wasn’t until around 1949 that the Little League idea went viral, at last affording countless parents nationwide the opportunity to live the American dream – the chance to act like a lunatic in public without reprisal.

The corollary point then, is that large numbers of major league players never joined a Little League, and never even had the chance to; and given that proviso, we need to reassemble the percentages along Little League/pre-Little League lines, and then see how the numbers break.

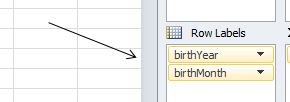

So let’s proceed. First, click back on USA in the filter and drag the birthYear field into the Row Labels area, stacking it atop the birthMonth field already in place, because we want Year to serve as the superordinate breakout field as it were, such that years break out into months, as you’ll see:

(By the way – the Compact Form Report Layout is perhaps the most legible one at this point. To introduce it to the pivot table click PivotTable Tools > Design tab > Report Layout > Compact Form.)

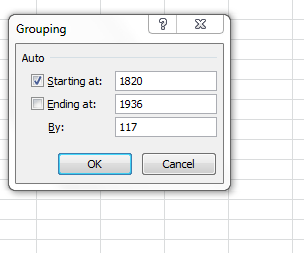

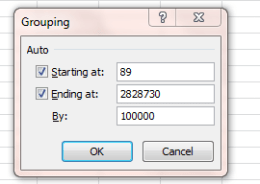

Then click on any year and click PivotTable Tools (if necessary) > Options > Group Selection. In the resulting window type

OK – I sense a need to explain myself here. In order to demarcate pre and post-Little League major league players, we need to identify the start year from which boys (they would be boys, here) began to have a fighting chance to sign on to a Little League team. If the League went big-time around 1949, I’m estimating (at least for starters) that 12-year-olds – that is, those kids born in 1937 – could have plausibly made themselves available to suit up. That’s an educated guess, of course, but it’ll do for now. In light of that conjecture, I’m thus interested in grouping players born before 1937 – hence the two years entered above. The 117 counts the number of years spanning 1820 and 1936, entered here because we want the ensuing pivot table results to bundle all 117 years into a unitary total (you’ll see what that means momentarily).

Click OK, and you should see:

No, that’s not what we want to see, because Excel continues to aggregate data for all the years, bunching the post-1936 birth years into a residual category that completely confounds the outcome we’re seeking. But by clicking the filter down arrow hard by the Row Labels title and ticking >1937 off, we get

Well, that’s interesting too – because an August birth-month differential persists, not as pronouncedly as for the post-1936 years, to be sure, but it’s there.

Of course you can fool around with different Ending At years in the Grouping window to varied effect. When I group for birth years between 1820 (the oldest recorded birth year in the Lahman database) and 1900, the aggregates break rather differently and incline toward birth month parity:

But if I establish the upper year limit at 1920 – and virtually no boy born that year or earlier played in Little League – August still pulls into second place behind October, at 9.18% (the continuing prominence of October in these snapshots might be worth pursuing as well). Explanations anyone?

Well, you can think about all this over the weekend. As for me, I’m thinking about my brother – pretty decent Little Leaguer, and born in…August. He became a neurologist, heads a division at the FDA, gets his name in the Times now and then. But yo, bro’ – maybe you should get back into the batting cage and starting taking your hacks – your next career move awaits.