Before I screw up the temerity to forward a new and different set of handedness data in your direction, a few residual thoughts on the data under our current consideration might be worth thinking through.

The Lefthander Birthdates Analysis sheet charts a number of data series in the interests of promoting birth-total comparisons, including therein a Flat series that presumably draws a baseline of birth-month expectations defaulting to a “chance”-driven birth distribution. That series simply divides 100% by 12, thus granting an 8.3% birth share to each month; but of course the variable day allotment of the months should manufacture a set of variable fractions instead. Each month should have submitted its days to a divisor of 365.25, the approximate average duration of each year (there’s that leap year in there); and so the 31-day months would chance-predict an 8.49% birth proportion, 30-day entries would figure to 8.21%, and the 28.25-day February predicts 7.73%. It thus seems to me, then, that the baseline is a wavy one. (Note also that the chart’s country birth percentages emanate from governmentally-compiled, not Lefthanders Club survey data).

Moreover, I would allow that the Daily Analysis sheet – a breakout of respondent birth dates by each of a year’s potential 366 days (below, in excerpt)–

| 0101 |

7 |

| 0102 |

6 |

| 0103 |

11 |

| 0104 |

9 |

| 0105 |

14 |

| 0106 |

7 |

| 0107 |

14 |

| 0108 |

8 |

| 0109 |

13 |

| 0110 |

11 |

| 0111 |

13 |

| 0112 |

8 |

| 0113 |

13 |

| 0114 |

9 |

| 0115 |

11 |

| 0116 |

7 |

| 0117 |

6 |

| 0118 |

9 |

| 0119 |

7 |

| 0120 |

15 |

| 0121 |

6 |

| 0122 |

7 |

| 0123 |

8 |

could have, and probably should have, been entrusted to a pivot table:

Row Labels: Date (Grouped by days only)

Values: Date (count)

Because these Daily Analysis dates seemed to have been appropriated from the text-populated MonthDay field in the birthday-dates master sheet, the days can’t be grouped, for example.

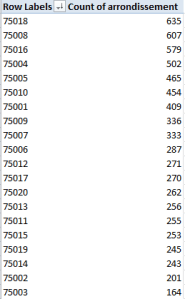

In any case, the Left Hander numbers declare an August plurality, though consecutive months plot a rather jittery trajectory (this is my pivot table):

And what could all of the above mean? Remember the survey’s raison d’etre: to associate the incidence of left-handedness (however that trait might be denoted) with certain birth months. Granted, I’m not a neurologist, but if handedness is in fact month-bound I’m at a bit of a loss as to how to reconcile the oscillation in handedness percentages across adjacent months, and on the face of it the notion that manual preferences should somehow exhibit seasonality sounds like something of a reach – with either hand. Do we want to run with the proposition that children born in late August experience a stepped-up gestational likelihood they’ll emerge lefthanded relative, say, to a babies born in the first week of September? And if so, why?

But there are additional considerations. Is the Lefthander Club survey sample skewed? Probably. After all, its respondents were self-selectees, the sort of volunteer-led cohort that bodes badly for samples. But why, on the other hand, should self-selection even matter here? Why should a lefthanded respondent’s decision to respond somehow tie itself to the month in which she or he was born? Skewed samples can cause all kinds of problems, but only when the skew pushes directly at the theme with which the survey is concerned. Asking a readership to complete a questionnaire on political party affiliation might inspire the members of one party to tick those boxes more eagerliy than the other. Indeed, a given readership itself might very well be skewed (think of the Literary Digest 1936 presidential survey debacle) to begin with. But what selection contaminants could befoul a handedness-by-month survey? Why should the August-born be prepared to assert their birth month with a conspicuous, invidious ardor? What’s in it for them?

The point is that not every variable impacts every equation, and the default premise grounding the lefthander survey – that respondents have no particular reason to extol this or that birth month, along with other conceivable sources of skewedness – for example, a greater willingness of women to participate – shouldn’t alloy the birth-month numbers.

And so we might be ready to declare the survey sample functionally random. But there is a complication, apart from the necessary considerations of sample size (and it does appear as if the monthly variations are statistically significant, at least at first glance), one that was brought to my attention by Chris McManus, an authority on handedness who teaches at the University College of the University of London (he’s also cited by the Lefthander’s newsletter).

If you return to the Daily Analysis sheet, row 226 looms large:

That’s August 13th – which happens to be International Left Handers Day, the day appearing on the birth certificates of 1.04% of the American respondents and .94% of the British submitters. This, then, appears to exemplify a case of self-selection that does contribute to a meaningful skew, and Professor McManus adds that once the August effect is chased from the data the remaining months fail to comport significantly with handedness.

But I still haven’t said anything about that alternative data set. I think we need a third installment.