Quick: what’s the first thing that comes to mind when someone asks you to name a classic, defining use for Excel?

OK, ok; the very first thing that’ll streak across your medulla upon hearing the question is: what sort of dweeb would snap my latte-laced reverie by even bothering to ask such a thing? Granted. But even after you settle yourself down, your second answer assuredly won’t read something like this: word counts.

You see, Excel doesn’t do word counts, or isn’t supposed to. That sort of task is properly, and obviously, delegated to Word’s formidable text-handling charge, and the whole silly matter should end right then and there.

But Excel can count words, if you’re prepared to go one-on-one with some prolix, Rube Goldberg-circumnavigational, parenthesis-lousy formulas. Still the prior question remains: why bother?

And it’s a good question. By itself one would indeed be hard-pressed to justify the enterprise, particularly when Word beams that very information to its status bar ubiquitously, for all to see all the time.

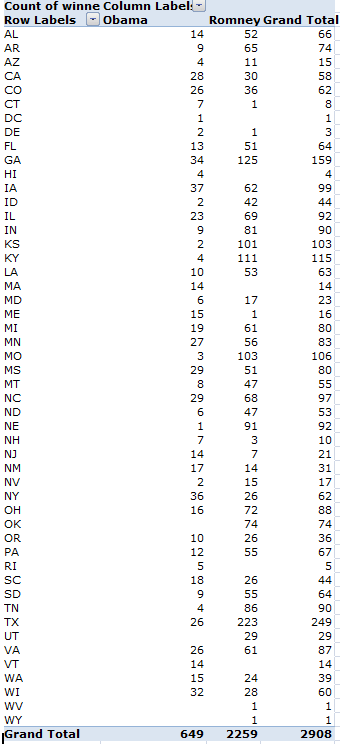

But when pressed into a supporting role in a kind of content analysis, spreadsheet word counts start to matter more. Publications such as the New York Times comb speeches for the incidence of key words (they pursued this kind of work during the 2012 presidential nominating conventions), and word incidence divided by all speech words can deliver some telling fractions. For example – Mitt Romney uttered the word America and its variants (American, etc.) 93 times in his acceptance speech, the President 85 times in his. Romney’s America amounted to 2.27% of all his acceptance words, Obama’s 1.92% – strikingly comparable numbers.

Those stats come right at you from my very own workbook, and which I’m making available to you at

The book lets you copy and paste any text entry (be it a speech or any other excerpt, of course) and enter up to twenty key search terms, whose frequency of appearance in the text are automatically calculated (I’m sparing you the formulaic technicalities here, which would require a dedicated and prolonged treatment). And as a rule it should be that simple, although I need to add a couple of provisos.

To use the book, which demos Romney’s convention speech, just click the A column heading to select the column, and press Delete. Then locate your text excerpt and run through a standard copy and paste routine, pasting the data to cell A3. Don’t by bothered by any blank rows streaking through the text – the formulas can deal with those. Then just replace the demo search terms with your own, and note the counts and percentages.

And here are the provisos. First, because the word searches hunt instances of contiguous text, a search for “American” will also tap “American” and “Americans”, for example, and that error on the side of inclusiveness is typically a good thing; it plays a de facto search wild card, gathering word variants into the larger count. If, however, you want to search for “American” exclusively, type American.

Note then that a search for the word “the” – something you’re not going to be doing, I’d wager – will likewise pinpoint “breathe” and “their”, for example, and puff the search total misleadingly. Here you’d want to search for [space]the[space], thus isolating the desired term. On the other hand, you’ll miss “the.” as a result, and that’s stands as a problem, albeit a minute one.

Some other points, subtler ones. Many text excerpts will exhibit dashed clauses, e.g.,

Guess what – it’s raining outside.

And because the search formulas here develop the word count by totaling the spaces between words (and adding one at the end of every pasted line in the A column), that dash above will be accorded word status, again distending the count, this time by just a bit. If you want to check for and zap any dashes the fastest tack is to

paste the text into Word, summon the Find and Replace feature (shortcut: Ctrl-H), and enter a dash in the Find what field, and nothing at all in Replace with:

Just click Replace All, and then copy the excerpt into A3. (Note: if you suspect other, extended-width dashes are poking about as well, you may need to play with the Find what: specification, e.g., entering –.)

Another one. Some speech transcripts interpolate extra-textual asides between actual speech content, e.g.

(Applause).

You’ll want to repel these insurgent glosses, and once again Find and Replace can carry the day. In first click the More button holding down the window’s left corner and select Use Wildcards. Then enter this curiosity in Find what:

\(*\)

That patch of code canvasses every open and closed parenthesis (or bracket, as they term it in the UK) in the text, along with any text in between. Again, omit Replace with: and click Replace All. I should add that Word’s Find coding options are populous, and can get rather scary. See for starters

http://office.microsoft.com/en-gb/word-help/find-and-replace-text-or-other-items-HP005189433.aspx.

But it can get scarier than that. In any case, note that you may have to do some additional vetting and gives the bum’s rush to some other text intruders, too; some of these are probably best disposed of with a simple pat of the Delete key.

In any case, I’ll humbly submit that the word search workbook is swift, easy to use and has a role to play in various investigative tasks. Get back to me with any comments or questions – and the helpline is toll-free.