What do chess, scrabble, bingo, planet earth, and Excel have in common? Not much, save one central, jointly indispensable commonality: all of the above conceive of themselves as grids of various vastness, cubed into coordinates named by the junctions of their row and columns.

The earthly cell references are longitudes and latitudes, pinpointing the world’s intersections under the descriptive auspices of one of two vocabularies. One speaks the language of N/S and E/W, e.g., Boston=42◦21◦N/71◦03◦E, the other a language of continuum, Boston: 42.321597/-71.09115, the minuses deriving from positions either east of the Greenwich meridian and/or south of the equator.

It’s the latter dialect that serves spreadsheet cartographers well, its values strung along a unitary span. And what’s to be made of all this? To begin to answer that quasi-rhetorical question, let’s return to the Washington DC crime data at which we looked a number of posts ago (August 14). We subjected the data there to a series of time-based scrutinies, e.g., crimes by day of the week and the like. But the data also plot the crimes in space, by companioning them with their latitudes and longitudes.

So here then is the plan: why not break out the data by location, lining a pivot table Row Labels area with latitudes and its perpendicular, the Column Labels area, wth longitudes? Each cell in the table, marking the crossroad of a latitude and longitude, would thus be addressed in spatial terms, and in a manner that would more-or-less respect the proportionate distances between coordinates. In other words, we could in effect literally map the data – a kind of character-based data viz, the map comprising the values slotted in their cells. Then tincture the numbers with a conditional format (the discussion of which is planned for Part 2) and you’ve heat-mapped the table.

To start afresh, you can download the DC data here:

Once accessed, the workbook-map gestates into shape pretty easily – once we get past a couple of provisos. You’ll note that the latitudes and longitudes (let’s call them lats and longs henceforth, if those abridgements aren’t too cute. But if you’re already acquiescing in the z in data “viz”, you’ll doubtless cut me this slack) are extended to 12 decimal points, in the interests of placing the data precisely at the crime scene. But that very exactitude militates against useful data generalization. We want to able to abstract the data slightly upwards, coarsening the lats and longs into larger districts across which crime patterns might, or might not, coalesce. When you consider that one degree of longitude in DC reaches across about 54 miles (see the web site http://andrew.hedges.name/experiments/haversine/ for some neat fill-in-the-blanks lat/long distance calculations), drilling that span down 14 decimal places will probably yield a unit measurable with a ruler.

As a result, I’ll propose (of course all is changeable in these regards) that we round the lats and longs to 3 places. If I’ve done the math reasonably correctly, that’ll take us to thousandths of a degree, for longs in DC about .054 miles, or about 260 feet – still pretty drilled-down, but a workable start. Remember of course that a simple reformat won’t impose any substantive, valuational change upon the numbers. Formatting

38.89345352158069

as

38.893

Will still preserve all those 14-decimal points, and formulas will continue to work with them. All you will have changed is the number’s appearance. Rather, we need the ROUND function:

=ROUND(cell reference,number of decimal points to round off)

a mechanism that changes the substantive value of the number being rounded. Thus if the prolix number above sits back in cell A1 then

=ROUND(A1,3)

will bring about an actual, usable 38.893. So let’s do the following: select the K and L columns, these sporting superfluous city information, and delete their contents. Then name K Lat and L Long. In K2 write

=ROUND(I2,3)

and in L2

=ROUND(J2,3)

And copy both down their respective columns (you may want to widen L in order to be able to view the 3 decimal points).

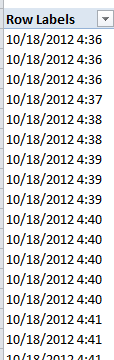

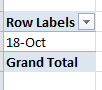

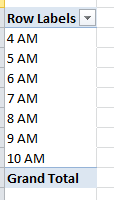

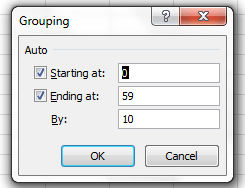

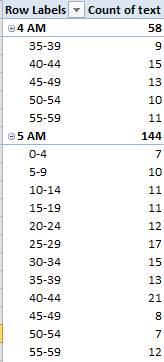

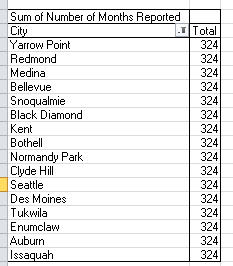

Then it’s pivot-table time. Put the table in place in drag LAT to the Row Labels area. I get 178 values spurting downwards, probably too many to support meaningful generalizations. Thus we can group the lats by intervals of .01, although needless to say you can fool around with other increments (recall that our rounding offs above acted upon individual lats. Here we’re enfolding several lats into a manageable cohort. Nevertheless, rounding itself does enforce a manner of grouping, as well. Rounding 38.9913 and 38.9911 to 3 decimals renders them identical). Click anywhere among the lat data and click PivotTable Tools > Options > Group Selection. Type 0.01 in the By: field. You should see:

Now we can move to do something similar to the longitudes. Drag LONG to the Column Labels area, and the results will bolt all the way to the GW column (is that George Washington?), rather a way-out venue. Again, click among the data and return to Group Selection and an 0.01 reading. That compresses the grouped numbers back to the V column.

Then drag OFFENSE into the Values area. You should see something like this (my shot is excerpted):

You’re starting to get the idea. We really have in effect mapped the data against their spatial correspondences; note the clustering of crimes around the -77.034/-77.024 longitude, for example, as well as the numerous blank spaces across the table, which may – probably – denote uninhabited precincts. That is to be researched, of course, but in any case the point has been established – namely that DC crimes are by no means randomly dispersed (of course a closer consideration would require a scaling of crime numbers against the populations of the locational groupings above; and by adding a second OFFENSE entry, this time to the Report Filter area, specific crime-type distributions could be bared).

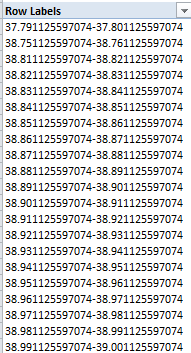

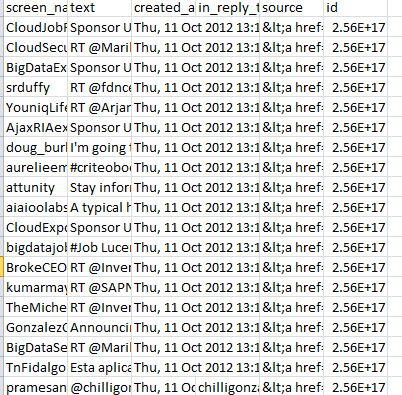

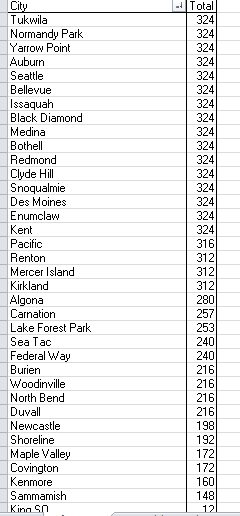

Now for a final observation today on the Group Selection feature. I had recommended a rounding of the workbook lats and longs to a 3-decimal point bore, in order to tailor the physical spaces with which we’ve been working into what could be termed sociologically practicable sizes. But there’s another, more strictly operational reason to round off: if you toss long-decimal values into a pivot table and proceed to group them, you surrender all formatting rights to the outcome. That is, if you had grouped the native 14-decimal point values and attempted to group them, they’d look something like this:

And the point is that the hallucinogenic tableau above can’t be formatted any further. The grouping absconds with the values’ numeric status and relegates them to inoperable, inert text. If you doubt me, try formatting them.

And if you succeed, you can call me – collect.