It’s Greensboro North Carolina’s turn to admit itself to the open-data fold, and it’s been stocking its shelves with a range of reports on the city’s efforts at civic betterment, all spread behind the familiar aegis of the Socrata interface.

One such report – a large one at 67-or-so megabytes and 211,000 records – posts call-response information from Greensboro’s fire department, dating the communications back to July 1, 2010, and made available here:

https://data.greensboro-nc.gov/browse?q=fire

If you encounter the “Datasets have a new look!” text box click OK, click the Download button, and proceed to CSV for Excel.

And as with all such weighty data sets one might first want to adjudge its 58 fields for parameters that one could properly deem analytically dispensable, e.g., fields not likely to contribute to your understanding of the call activity. But here I’d err on the side of inclusiveness; save the first two incident id and number fields and perhaps the incident address data at the set’s outer reaches (and the very last, incontrovertibly pointless Location field, whose information already features in the Latitude and Longitude columns), most of the fields appear to hold some reportorial potential, provided one learns how to interpret what they mean to say, and at the same time comes to terms with the fact that a great many of their cells are vacant. (By hovering over a field’s i icon you’ll learn something more about its informational remit.) In addition, several fields – Month, Day, and Week, for example – could have been formulaically derived as needed, but Greensboro has kindly brought those data to you without having been asked.

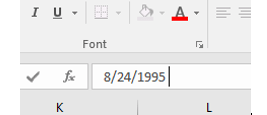

In any case, it’s the date/time data that bulk particularly large among the records and that could stand a bit of introductory elucidation. First, the CallProcessingTime data realize themselves via a simple subtraction of the corresponding 911CenterReceived time from the AlarmDate (and don’t be misled by that header; there’s time data in there, too)- Thus the call processing time of 15 seconds in K2 (its original columnar location, one preceding any field deletions you may have effected), simply derives from a taking of O2 from P2. That is, call processing paces off the interval spanning the receipt of a 911 call and the dispatching of an alarm. Subtract 7/2/2010 11:38:17 AM from 7/2/2010 11:38:32 AM, and you get 15 seconds.

Well, that’s obvious, but peer beneath the 00:15 result atop K2 and you’ll be met with a less-than-evident 12:00:15 AM. You’ve thereby exposed yourself to the dual identity of time data.

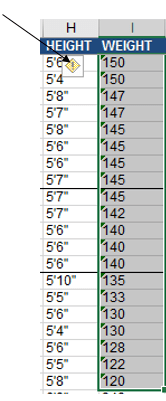

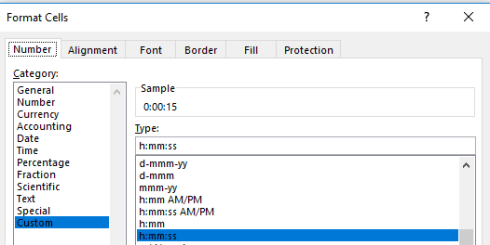

Subtract one time datum from another and you will indeed have calculated the desired duration, but that duration also counts itself against a midnight baseline. Thus Excel regards 15 seconds as both the elapsing of that period of time – as well as a 15-second passage from the day’s inception point of midnight (which could be alternatively expressed as 00:00). Examine the format of K2 and you’ll see:

And that’s how Excel defaults this kind of data entry, even as an inspection of the Formula Bar’s turns up 12:00:15.

That feature, proceeds by Excel’s standard scheme of things, however ; a more problematic field concern besets AlarmHour, which presumably plucks its information from AlarmDate (an equivocally named field to be sure, as it formats its data in time terms as well). Hours can of course be returned via a standard recourse to the HOUR function, so that =HOUR(P2) would yield the 11 we see hard-coded in N2. But many of the hour references here are simply wrong, starting with the value in N3. An alarm time of 3:51 AM should naturally evaluate to an hour of 3, not the 12-hour-later 15 actually borne by the cell. Somehow the hourly “equivalents” of 3:00 AM and 3:00 PM, for example, underwent some manner of substitution, and often; and that’s where you come in. Commandeer the first unfilled column and enter in row 2:

=HOUR(P2)

Copy all the way down, drop a Copy > Paste Values on the AlarmDate column, and then delete the formula data.

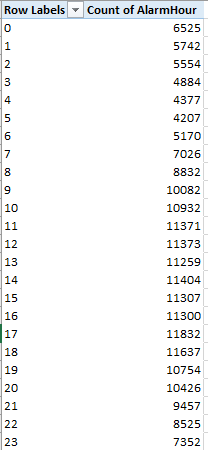

And once in place a number of obvious but meaningful pivot tables commend themselves, leading off with a breakout of the number of alarms by hour of the day:

Rows: AlarmHour

Values: AlarmHour (count)

I get:

Note the striking, even curiously, flat distribution of calls.

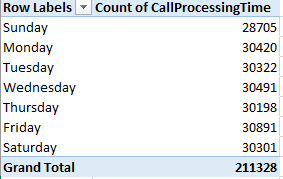

Next we could substitute day of week for hour, both for Rows and Values:

(Truth to be told, leaving AlarmHour in Values would have occasioned precisely the same results; because we’re counting call instances here, in effect any field fit into Values, provided all its rows are populated, would perform identically.)

Again, the inter-day totals exhibit an almost unnerving sameness. Could it really be that alarm soundings distribute themselves so evenly across the week? That’s a downright journalistic question, and could be put to the Greensboro data compilers.

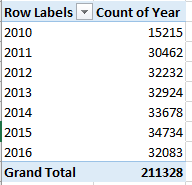

We could do the same for year (remember that the data for both 2010 and 2016 are incomplete, the numbers for the former year amounting to exactly half a year’s worth):

My data for this year take the calls through November 7; thus a linear projection for 2016 ups its sum to a new recorded high of 37,744.

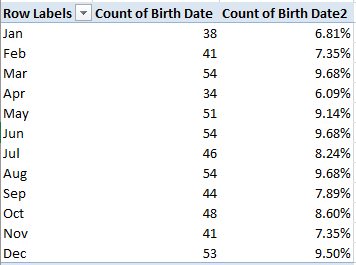

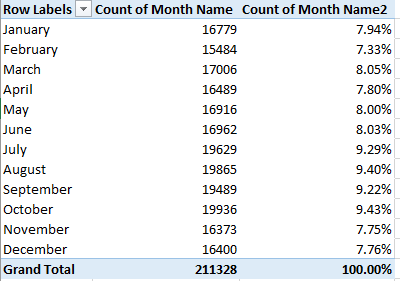

We could of course do much the same for month, understanding that those data transcend year boundaries, and as such promulgate a kind of measure of seasonality. We could back Month Name into the Values area twice, earmarking the second shipment for a Show Values As > % of Column Total:

The fall-off in calls during the winter months is indisputable, but note the peak in October, when a pull-back in temperatures there is underway. There’s a research question somewhere in there.

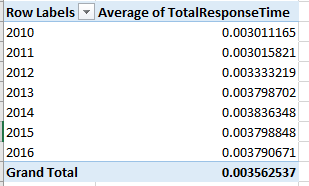

Of course more permutations avail, but in the interests of drawing a line somewhere, how about associating TotalResponseTime (a composite of the CallProcessingTime and ResponseTime in K and L, respectively) with year?

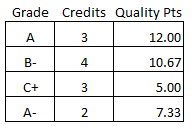

Return Year to Rows and push TotalResponseTime into Values (by Average) and you get:

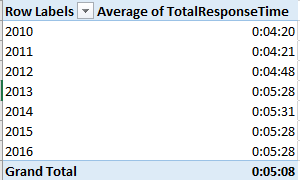

That’s not what you were looking for, but the pivot table defaults to the times’ actual numeric value, in which minutes are expressed as a decimalized portion of an 86,400-minute day. Right-click the averages, click Number format, and revisit the Custom h:mm:ss (or mm:ss, if you’re certain no response average exceeds an hour). I get

What we see is a general slowing of response times, though in fact the times have held remarkably constant across the last four years. But overall alarm responses now take 30 seconds longer than they did in 2012, and more than a minute from 2010. Does that matter? Probably, at least some of the time.

Note, on the other hand, the 1500 call processing times entered at 0 seconds and the 933 total response times set to the same zero figure. Those numbers await a journalist’s response.