No analysis of the Toronto 311 call data can press its task without firming its grasp of the meaning of the fields themselves, not all of which can be fairly described as self-evident.

Let’s see. Calls Offered appears to mean nothing other but calls received, and Calls Answered appears to mean precisely what it says – namely, a count of the calls which 311 operatives actually attended, though this measure does not want for ambiguity (Look here, in particular pages 10 and 11, for some of the definitional issues, along with a battery of critiques of the 311 operation). Exactly why the unanswered calls lurched into the void ain’t, as the song says, exactly clear, particularly in view of the fact that some of these may have been in fact mollified by recorded messages. Again, check the report linked above.) Call Answered %, in any case, simply divides Calls Answered by Calls Offered.

Service Level %, on the other hand, begs for clarification and enlightenment was kindly provided by Open Data’s Keith McDonald, who told me that the field records the “percent of received calls that is answered within the service level goal of 75 seconds”, an understanding that in turn calls for a rumination or two all its own. (Note: I appear to have misapprehended the Service Level %’s formulation, having originally, supposed “that, because the Service Level % often exceeds its companion Calls Answered %, Service Level adopts the less numerous Calls Answered as its denominator, and not Calls Offered. Thus if anything the Service percentages overstate 311’s responsiveness to its public, by discarding unanswered calls from the fraction. For example, the 100% Service Level boasted on January 2 obviously invokes the 2039 Calls Answered, since another 325 calls on the 2nd were never answered at all. You can’t extol a 100% Service Level for all 2264 calls if some of them simply weren’t responded to, for whatever reason.” However, read Keith McDonald’s comment below.)

Second, note that unlike the Calls Answered %, Service Level % presents itself in percent terms without pointedly identifying its numerator -Calls Answered times Service Level %. If, then, you go on to merely calculate the average of the Service Level percentages as set forth, you run the risk of appointing disproportionate weight to days with relatively few calls. I’d thus open a column between H and I, call it something like Calls Meeting Service Level, and enter in what is now H4:

=G4*E4

and copy it down I, remembering to mint the column in Number format, sans decimals. These quantities can now be properly summed and averaged, etc.., thus honoring their real contribution to any calculated whole.

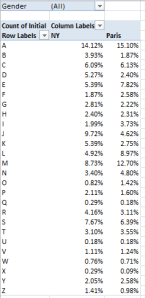

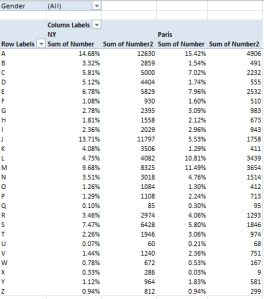

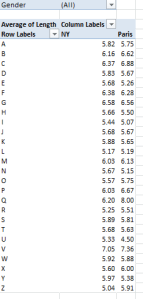

OK – so how about those service levels, say by Day of Week? We could try this:

Row Labels: Day of Week

Values: Calls Answered

Calls Meeting Service Level (both Sum. Note this field likewise requires a decimal-point reduction, because the round-off we executed earlier won’t extend to the pivot table. Remember that in any case these roundings only format the numbers, without transmuting their actual values.

And here we could cultivate a Calculated Field (see my August 22, 2013 post, for example, for some how-tos), called Service Pct or some such:

formatted perhaps in Percentage terms to two decimal places:

Not much variation here, the results baring a response consistency of sorts. Even the quieter Saturdays and Sundays cling to the 80% notch on the dial, goading questions about weekend staffing levels and call intake procedures. Indeed – correlating Calls Answered with Service Level %:

=CORREL(F4:F368,H4:H368)

evaluates to an indifferent -.135, or a very small negative association between numbers of calls and response alacrity, per the 311 guidlines.

But days of the week are interlaced across the year, after all, and as such might be driven by more potent seasonal currents. If we substitute Date for Day of Week in Row Labels, and group the former by Month:

Here the picture changes. Service percentages associate far more tightly with call volume (operationalized here by Calls Answered), at -.55 (I simply ran a CORREL with the 12 Calls Answered and Service Pct cells above); and that makes rather straightforward sense. More calls to answer, longer response times. And if you add Calls Offered to the above table (Sum, again) and correlate that parameter with Service Pct, you’ll get -.716, a pretty decisive resonance. The more calls in toto, the fewer that penetrate the 75-second transom.

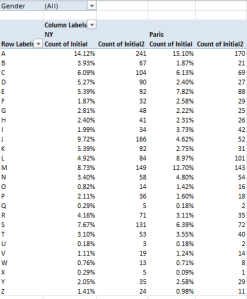

What about Calls Abandoned > 30 seconds? According to Keith McDonald, “Abandoned means caller hung up. In high call waiting periods, customers hear the upfront message and decide to hang up [following a wait of at least 30 seconds, apparently. I’m not sure about callers who gave up sooner].” (Note as well that Calls Abandoned + Calls Answered won’t add up to Calls Offered.) Here Calls Abandoned % builds its percentages atop the Calls Offered denominator, and the abandonment numbers seem to range all over the place. Time for a more systematic look, e.g:

Row Labels: Date (grouped by Month)

Values: Calls Offered (Sum)

Calls Abandoned > 30 sec (Sum)

Correlation between Calls Offered and Calls Abandoned: a ringing .745. Not surprising, perhaps, but when the numbers jibe with common sense – a less-than-ineluctable state of the data – it’s kind of pleasing. And if you slot in Average Speed of Answer (sec) (summarized by Average):

Correlation between that field and Calls Offered: a mighty .881.

Doesn’t a certain existential charm devolve upon confirmations of the obvious?