There are spreadsheets with problems, if I may be so judgmental, and then there are spreadsheets with meta-problems. I see a hand back there requesting clarification.

It’s like this: much of the expository thrust of this blog has dedicated itself to the former sorts of problems – issues of data quality, and formulaic remedies to other issues. But sometimes even a perfectly sound agglomeration of data begins to act up, when it’s asked to live peaceably with another batch of otherwise perfectly sound data.

It happens. It happens when you want, or need, to – and I use this verb with some hesitation – consolidate two kindred but not –quite-identical sheets into a larger totality (and let’s leave Excel’s Consolidate feature out of this). The meta-problem, then is reconciliation,

And it isn’t as abstruse as it sounds. A case in point: the birth-name data compiled by the municipalities of New York and Paris. There may be any number of piquant sociolinguistic conclusions to be learned from these data, but the data aren’t quite yet fit for the cross-cultural comparative aims we intend for them.

For one thing, the New York data comprises two gender-distributed workbooks; the Paris sheet is of a piece, assigning instead a defining field for gender (as do the New York data, by the way, perhaps redundantly):

Liste des prénoms 2004-2012(1)

2009_Popular_Birth_Names__Female_

2009_Popular_Birth_Names__Male_

The task, or tasks, then, that prefigure any subsequent analysis: to normalize the data so that they read the same way all the way down, and play on, or with, the same fields.

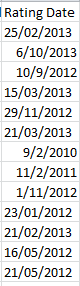

At least these steps aren’t particularly sequence-dependent. First, then, we need to understand that even as the Paris data report birth names from 2004-2012, the New York names avail only for 2009, thus tapering the comparison range to but one year – and as such, the Paris year of birth field (annee) doesn’t spur the narrative, and so you want to disassociate the 2009 names from their companion data, which can’t be compared across the two cities. I can think of several ways to make this happen; perhaps the trouble-freest would have you auto-filter the 2009 names, whereupon you’d copy them to a new sheet – and why not a sheet in the same Paris workbook? I can then simply delete the annee column, because again, all the names with which we want to work, after all, bear the 2009 provenance.

Next, given that the Paris sheet abbreviates gender (or sexe – the field headings are French, of course) I’d turn to the New York sheets and run a find and replace through their gender data, replacing Female and Male with their respective initials. (I’m not bothered by the all-capped New York names, though a restoration of these is just a PROPER function away. =PROPER(B2) on the Female birth name sheet, for example, will restyle ISABELLA into Isabella.).

I’d then copy-paste all the New York gender identifications into the next available Sexe cell into this new sheet (I’ll rename the field Gender), and follow through with a parallel copy-paste of the New York names, taking pains of course to line up each name with its gender. I’d also ignore the New York Rank data; these are nowhere to be found among the French names, and we can order all the data from both countries in a pivot table in any case. And of course you also have to copy the New York name counts to our sheet-in-the-making, again seeing to it that each number is properly affiliated with its name. And while we’re at it, I can rename prenoms Name, and nombre Number (if you parle Anglais).

Now our working fields – Name, Number, and Gender – need be staked to a fourth one, one that differentiates the pair of cities whose names we want to compare. Thus we can type City in Row 1 of the next free column, Enter Paris in what for me at least is D2, and copy it all the way to row 1127, or whichever cell on your sheet stores the last French name. Then enter NY one row down and copy to your last New York name, which for me tucks itself into row 2834. (You can tell where the New York names start; they’re the ones puffed up in capitals.)

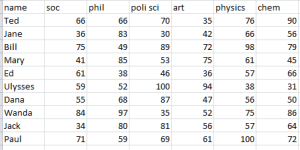

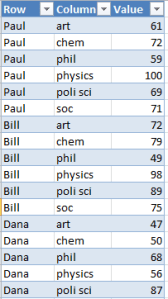

All this to-and-froing means the sheet under construction looks something like this (depending on how or if you’ve sorted the data in any way), in its upper reaches:

And irrepressible lad that I am, it seems to me that a minting of two additional fields could usefully inform the data. Because we might want to learn something about inter-city first-initial naming preferences, we can call the next available column Initial and enter in what is for me E2:

=LEFT(A2,1)

And of course copy all the way down.

We might also be concerned to do some trendspotting about name lengths. If so, move on to column F, name it Length, and type in F2:

=LEN(A2)

and copy accordingly.

Now our reconditioned sheet – an admirably lean composite, all of whose fields are eminently usable and worth a breakout or two – looks good to go.

But before we go, there are a couple of yellow lights at which we need to pause. Note that the New York data calls for a name-reporting minimum of ten births; that is, a given name must identify at least ten recipients before it achieves a listing. The corresponding qualification for the Paris list is five (though the Open Paris website seems to draw the line at six). These floors, even as they’re pitched at different elevations, cache an unknown census of births and names. It’s not inconceivable that a notably large number of babies inherited a notably large numbers of names, each of which was conferred upon a few babies each. That missing cohort isn’t accounted for here.

The other yellow light flashes a bit more brightly. New York is far larger city than Paris, and so divulges far more reported births – 86,021 to the City of Light’s 31,809, to be exact. How that disparity can be reconciled needs to be thought about. So let’s start thinking.