“Call 111 when it’s less urgent than 999”, Britons are advised, sloganeering the National Health Service’s plea for self-determined, telephonic patient triage of the not-quite-emergency cases that are routed through the number. Confounded by a buzz of organizational and operational issues, 111 has yet to find its stride in the NHS space, but disagreeable realities notwithstanding, the Service has delivered nine worksheets worth of data on its work to the Guardian’s DataBlog. It’s here, in Excel mode:

Lots of stuff there and because there is, and because the field names stamped atop NHS 111’s myriad columns understate the larger narrative sheathing the data, the workbook could do with a supplementary, textual legend (see the Guardian piece paired with the data). Put another, many of the field names are hard to understand. But granting that preliminary caveat, let’s steal a few looks at the spreadsheet, qua spreadsheet.

With respect to the All Sites sheet, there is the matter of all those blank rows streaking through the data, a classic bugaboo which nevertheless may or may not grant us cause to cavil. Because it appears as if the data are not of a piece – that is, they mean to disseminate a range of disparate truths about the 111 clientele in discrete sections – those rows are perhaps acceptably and merely punctuational, simply marking off bundles of stand-alone stats from one another:

In other words, All Sites doesn’t comprise the standard-issue data set of uniformly-fielded records, but rather an assortment of mini-disclosures inhabiting isolated spaces down and across. Worksheets such as these make me nervous – too many moving parts grinding in different directions telling too many different tales; but that’s what it is, and as such I don’t think the data there can be taken much further. Don’t even think about pivot tabling any or all of that, for example. And the captions in the B column need clarificatory work too, in my layman’s estimation (note the “more detailed description” footnote in A126, but I’m not sure where the “About MDS” page is to be found).

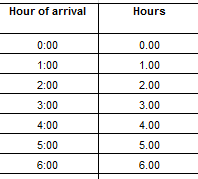

And there’s something else on All Sites that’s tugging at your pants (or trouser, if you’re reading this in the UK) leg in search of attention. Look, for example, at the time data visited upon rows 39, 85, and 89 (and elsewhere in the workbook). You’re seeing patient waiting times that’ve been dressed up –wrongly – in time-of-day formats (note: I have apprised the Guardian about this issue, and the format has since been remedied).

That 12:04:13 AM wants to report 4:13, but because it’s been customized to effect the h:mm:ss AM/PM format, what are in fact duration data present themselves as clock time. What All Sites really wants to do is confer this format

mm:ss

upon the cells, thus repackaging the data in minutes and seconds alone.

Moving right along, drop your cell pointer on D50 in the Providers-YTData sheet, and observe the value 3738.0018 beckoning in the Formula Bar. A curious entry, as it endeavors to count the number of survey respondents declaring themselves Very Satisfied with the 111 Experience – and statistical bromides aside, that .0018 needs to be explained, along with the other fractional demographics studding the D column. Perhaps these residua spring from formulaic results, though I can’t explain why these totals need issue from a calculated source in the first place. (The workbook in general is remarkably formula-free.) In any event, I’d deem it proper to ask after these decimals.

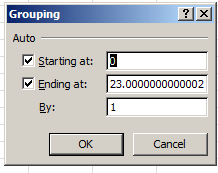

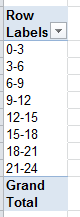

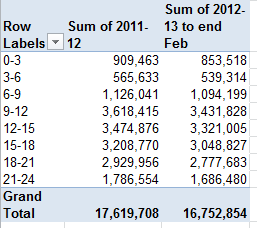

Turning to Category A Calls, you’ll note the Year field data fused into merged cells, whose neat presentational effect nevertheless stanches their analytical utility (and these are text, besides). These vertical headers can’t be joined up to any particular record, and anyway the date data in Month do furnish usable per-record year data (yes; they’re actual dates). And you’ll find the same merge effect in all the sheets to the right of Category A Calls.

We could also cite another oft-perpetrated data entry misstep in Category A – The yearly totals that have taken their place among the bona fide per-month data records. We’ve discussed this complication before; the point is that you can’t really work with total-row data, because summing or pivot tabling them has the effect of totalling all the contributory numbers twice. If the NHS asked me – and I can confirm that they haven’t – I’d unmerge the year cells, or more profitably, go ahead and delete the field – along with those totals records.

One more rumination, this one peculiar to the Calls closed without transport sheet: It appears as if the numbers in the “Number of calls resolved by telephone advice” and the “All emergency calls that receive a face-to-face response from the ambulance service” fields should yield the “All emergency calls that receive a telephone or face-to-face response from the ambulance service” figures for each record (are these fields starting to sound alike?) – but they don’t, not quite; and these discrepancies need to be explained, too.

Explanations, anyone?