Thematic continuity must be served, and so before we push this transit conceit to the breaking point we may as well redirect our squinty, subterranean gaze from Paris way east to New York’s subway system, 468 stops worth of data yearning to be crunched.

One such collection, amassed (and don’t you dare say “curated”; I’m circulating a petition calling for a six-month embargo on the term, and I know I can count on your support) by New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Association, counts weekday average daily ridership figures for the each of the system’s stops through the years 2007 and 2012, but presents a couple of preparatory challenges to the spreadsheet adept en route. Here it is:

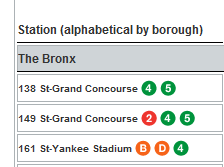

The stops are columned beneath the city borough name in which they’re positioned (four boroughs in this case; Staten Island has no subways), and those names are problematic; they occupy rows otherwise properly devoted to actual records, and their Otherness compromises the data. In short, borough name rows need to be deleted – at least eventually.

At the same time, however, you might well want to break out rider data along the borough parameter, and so you’ll want to interpolate a new column recording that identifier to the left of the sheet, by shoehorning what is to become the new A column to the left of the current one, calling it Borough, and entering the appropriate borough alongside the station name. There are a couple of ways of executing that task; a swift, formulaic strategy is to simply enter The Bronx in what is now A2, and enter in A3:

=IF(COUNT(C2)=0,B3,A2)

What exactly is this formula doing? It’s premised on the notion that any cell in what was the original A column that houses a borough name records no other data across its associated columns, or as operationalized more specifically in the above expression, there’s nothing in the C column. If that be the case, then the entry in B is returned – that is, the borough name. If the condition isn’t satisfied – that is, if the relevant C cell does contain some value – the cell references the contents immediately above it – the current borough name in force. Thus only when a new borough name appears down the B column does the formula introduce a correspondingly new name. Then run the results through a copy> paste values routine, and then delete rows 2, 71, 229, and 348 – the ones containing the borough names.

Now there’s another formulaic nicety out there angling for our attention. You’ll recall in last week’s post how the Paris Metro workbook parsed its multi-line stops, plugging each line into a discrete column:

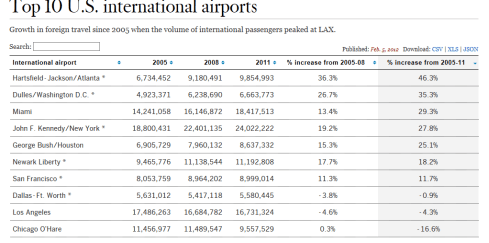

You’ll recall in turn the round of hoop-jumping through which we pranced in order to be able to develop a count of the shared lines per stop. But the New York data are different, appearing to code each line-per stop with the textual proxy “icon”, and in the very cell in which the station name is cited:

To picture how “icon” is transmuted into its graphical, literally iconic state, note this shot from the publication in which the stops listing appears:

Getting back to our spreadsheet proper, our interest then is in some way assembling a similar lines-per-stop total – by somehow counting the number of times in which the word “icon” figures in each stop record. We see, for example, that the 149 St-Grand Concourse entry features “icon” three times, befitting the three lines sharing that stop.

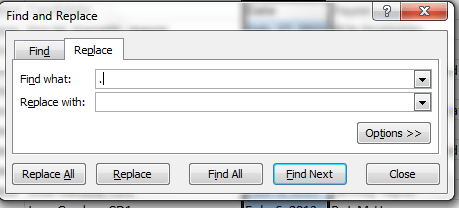

How do we do this? We do it by commissioning the little-used but trenchant SUBSTITUTE function. SUBSTITUTE finds every instance of a text expression within a cell and by default substitutes whatever replacement suits your fancy. Thus, for example, if cell A3 contains

It’s raining outside. When it’s raining I get wet.

And I want to substitute every instance of “raining” with “pouring”, I’d write, in another cell:

=SUBSTITUTE(A3,”raining”,”pouring”)

In our case, we want to:

1. Substitute every instance of the word “icon” with “iconx”.

2. Subtract the length of that result from the length of the original station expression. Thus if the word icon appears twice in a cell, thus signifying two subway lines boring through the stop, substituting every “icon” with “iconx” will found a new expression that’s two characters longer than the original – attesting to two lines.

Try it. Introduce a new column between the current B and C, head it Lines per Stop, and enter in what is now C2 (remember we’d deleted the original row 2, the one containing the Bronx borough name):

=LEN(SUBSTITUTE(B2,”icon”,”iconx”))-LEN(B2)

You should realize the value 2, because the first station entry, 138 St-Grand Concourse, discloses two instances of the work “icon”. (Note: SUBSTITUTE defaults to case sensitivity; if you want to substitute the letter x for each instance of the letter i in the phrase “I like to swim”, in A3, the capital I will stand firm. In our case, however, all instances of “icon” are case-identical, and so facilitate the substitution. If you do want to override case sensitivity you need tack the UPPER function onto SUBSTITUTE, thus forcing case parity: =SUBSTITUTE(UPPER(A3),”I”,”X”). UPPER imposes that case on all characters in a cell. Of course, that will ratchet all cell text into the upper case.)

Then copy the above down the C column. And once that mission is accomplished, you can shift into data analysis mode.